If you’ve been around me for any period of time, you’ve probably heard me say that I find two common approaches to software development: the mathematician’s approach and the linguist’s approach. The mathematician views the software design process as an equation to balance and typically does incredibly well at problems relating to algorithms, analysis, and lower-level system domains. The linguist, on the other hand, views the process of creating software as an exposition - a way of communicating an abstract idea via a constrained medium such as a programming language. Both groups are useful and necessary: some of the worst code I have ever seen was written by individual with PhDs in computer science or mathematics; many an expressive program falls flat on its face when put under the most trivial of loads. I imagine that most of you already know to which camp I belong, but just in case there was any question, I unapologetically and undeniably belong to the linguists.

It has been that lens which has guided me over the years into a variety of different technology interests, from early relational databases, to XML, to REST, to - most recently - linked data and functional programming. All of these have held my attention, not for their purely technical properties, but for the clarity with which they describe their non-technical subject.

Linked data is a technology that has held my attention for some time now for two key reasons. First, I have come to believe that it is the most true real-world implementation of REST as described by Roy Fielding back at the turn of the millennium. Second, I believe that the elegance of RDF as a distributed graph enables an unmatched level of expressiveness for data.

How, you ask?

I would respond with a single word: inferencing.

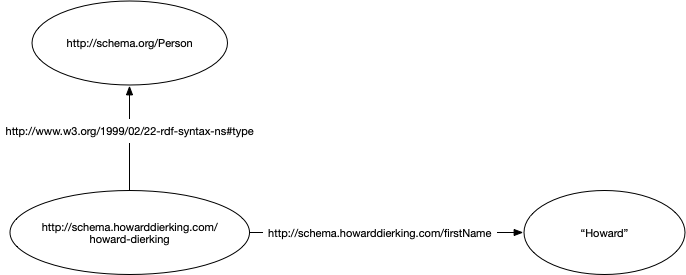

Linked data elegantly expresses data and metadata in a unified graph structure. Type definitions are little more than an exercise in associating a data node to a type-defining node with an edge defined by a well-known relationship type - typically by RDF itself.

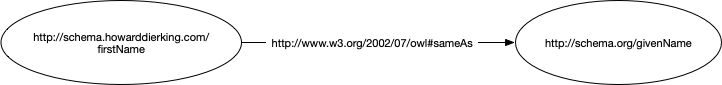

The simple graph abstraction, then, enables further elaboration of the metadata to capture relationships across different vocabularies. The most common vocabulary used for this type of specification is the W3C Web Ontology Language, or “OWL”.

The ability to model data in such an expressive manner is by itself a powerful thing. However, many RDF engines have functionality to “fill in the gaps” based on certain relationships from known vocabularies like OWL. The engine can use the specified relationships to produce new relationships - called inferences. Unsurprisingly, this process is called inferencing.

Now, this is all well and good in the abstract, but many folks I’ve spoken with about topics like linked data, RDF, and inferencing have had a harder time bridging the theory into something more concrete. So recently, I finally got around to putting a Javascript inferencing sample together using the rdflib.js engine and JSON-LD for the RDF serialization. The added benefit to using JSON-LD is that you can take all of the JSON snippets here and plug them into the JSON-LD playground to see what some of the expanded formats would look like - which is how they are seen by the RDF engine.

The sample is setup as two tests and a function whose job is to extract the first name from the document. Each test provides the function with a different document and the test needs to produce the same result for the different documents without any additional information.

describe('index', () => {

describe('#getFirstName', () => {

it('should return expected value for explicit triples', (done) => {

R.pipeP(subject.graphFor, subject.getFirstName)(doc1)

.then(actual => {

actual.should.eql('Howard');

done();

});

});

it('should return expected value for inferred triples', (done) => {

R.pipeP(subject.graphFor, subject.getFirstName)(doc2)

.then(actual => {

actual.should.eql('Howard');

done();

});

});

})

})

Both documents are written as JSON-LD. The first document contains little more than a small bit of namespacing metadata and the data itself

const doc1 = `{

"@context": {

"@base": "http://schema.howarddierking.com/",

"@vocab": "http://schema.org/"

},

"@type": "Person",

"@id": "/howard-dierking",

"name": "Howard Dierking",

"givenName": "Howard",

"familyName": "Dierking",

"url": "https://www.howarddierking.com"

}`;

The second document contains the same data as the first document, but also contains the OWL sameAs inferencing rule.

const inferred = `{

"@context": {

"@base": "http://schema.howarddierking.com/",

"@vocab": "http://schema.howarddierking.com/",

"s": "http://schema.org/",

"hd": "http://schema.howarddierking.com/",

"owl": "http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#"

},

"@graph": [

{

"@id": "hd:firstName",

"owl:sameAs": {"@id": "s:givenName"}

},

{

"@type": "Person",

"@id": "/howard-dierking",

"name": "Howard Dierking",

"firstName": "Howard",

"familyName": "Dierking",

"url": "https://www.howarddierking.com"

}

]

}`;

Out of the box, the rdflib.js library supports the sameAs rule which makes the first name extraction function trivially simple.

function getFirstName(g){

return first(

g.statementsMatching(undefined, SCHEMA_ORG('givenName'), undefined))

.object.value;

}

The code here does not need to be aware of every possible vocabulary that could be used to create a JSON-LD document - it only cares about the http://schema.org/givenName relationship as specified in schema.org. The sameAs inferencing rule between http://schema.howarddierking.com/firstName and http://schema.org/givenName caused rdflib.js to generate the inferred relationship, and thereby enabled the query for a value on the right side of a givenName relationship to succeed.

Wait, what??

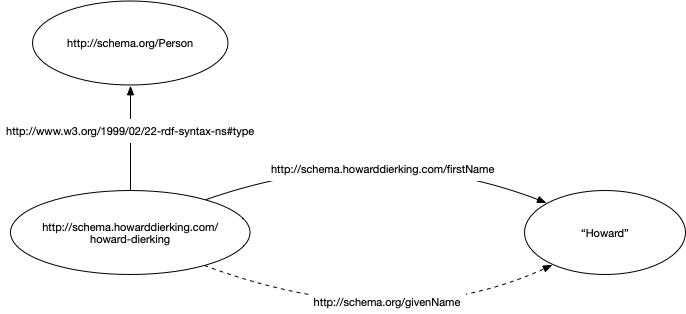

Here’s a format that might make it a little easier to see. Remember that a graph is little more than a collection of triples: subject | predicate | object. The JSON-LD document with inferencing looks like the following as triples.

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/firstName> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#sameAs> <http://schema.org/givenName> .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/familyName> "Dierking" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/firstName> "Howard" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/name> "Howard Dierking" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/url> "https://www.howarddierking.com" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/Person> .

When the inferencing rule is applied, the list has one new triple added.

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/firstName> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#sameAs> <http://schema.org/givenName> .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/familyName> "Dierking" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/firstName> "Howard" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/name> "Howard Dierking" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/url> "https://www.howarddierking.com" .

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.howarddierking.com/Person> .

# Inferred triple based on owl:sameAs

<http://schema.howarddierking.com/howard-dierking> <http://schema.org/givenName> "Howard" .

So there you have it. RDF inferencing enables us to specify relationships between metadata - even metadata from different vocabularies - and then use those relationships to process a variety of data without the lossiness of other popular methods like document transformations. This translates into more expressive, and I believe ultimately more robust data processing systems.